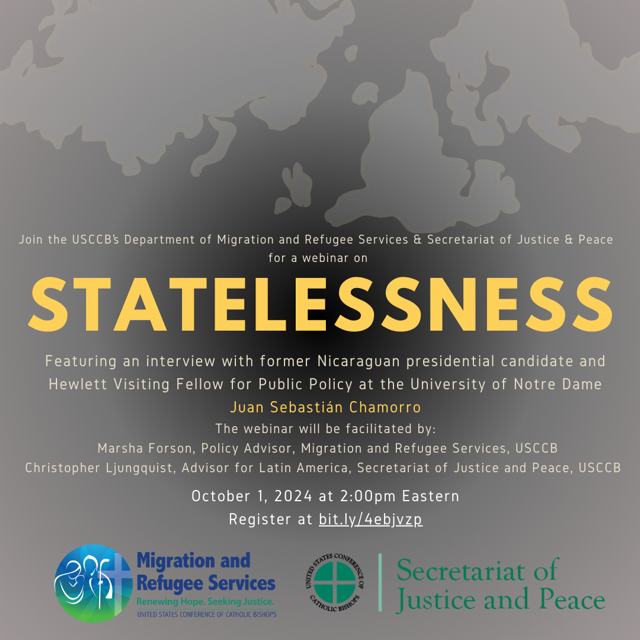

Webinar sponsored by the Department of Migration and Refugee Services

United States Conference of Catholic Bishops

October 1st, 2024.

I would like to thank the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops, the Department of Migration and Refugee Services and the Secretariat of Justice and Peace of the Conference for inviting me.

Thanks Christopher Ljungquist in particular, for caring about the situation in Nicaragua. If there is someone who knows how the situation of rights in Nicaragua has deteriorated since 2018, is you.

Citizenship is the main link between the individual and the state. The individual owes allegiance, loyalty and commitment, while the state entitles the individual with protection and rights. It brings both liberties and responsibilities. Without citizenship all rights are lost as this link is broken, leaving the individual under a condition of vulnerability and lack of legal protection.

Nationality, a broader concept, is, in addition of a legal status in international law, what associates us with a common history, traditions, language and land. It is an inherent part of the individual and therefore cannot be taken away because it is not something the individual has; it is the very social essence of what the individual is.

Statelessness, is the condition of a person of not being considered a national by any state. There are, according to the United Nations, about 4.4 million people in the condition of statelessness. It is sometimes overshadowed by exodus of people leaving a country, or terrible discrimation against entire communities, expelled of their countries or defined as second class citizens.

Statelessness can come from different causes. It may arise from a legal vacuum between the two modes of nationality jus soli and jus sanguini, as a result of discrimination based on gender, ethnicity, or administrative obstacles. It can also occur as the result of displacement to other countries.

In Latin America, the region that I come from, the most severe case of statelessness, in terms of people involved, is the case of Haitian immigrants in the Dominican Republic. Thousands of children born in the Dominican Republic, do not have Dominican nationality due to legal impediments.

Despite the multiple origins of statelessness, I will focus on one in particular: arbitrary deprivation of nationality. This action, prohibited by international law, is the result of an explicit action or policy by the state supposed to provide protection, to arbitrarily eliminate the link based on racial, ethnic, religious and political grounds.

I will be even more specific on the cases of deprivation of nationality based on political grounds, as it is the case that affected me and other 450 Nicaraguan individuals who have been stripped of our nationality by the regime of Daniel Ortega, just for political reasons.

Another large groups of Nicaraguans, probably in the thousands, are now de facto stateless persons as they have been denied entry into Nicaragua, thus leaving them in a legal limbo. For this reason we are calling the regime of Nicaragua a “factory of stateless people” as deprivation of nationality has become a common, unfortunate occurrence.

From arbitrary deprivation of nationality on political grounds derives the violations of all the fundamental rights given by citizenship, with the aggravating condition of state repression, persecution and violence. It is not a passive condition of State denial, but a consistent, deliberate action of a repressive regime to not just eliminate any kind of legal bond, but to attack and infringe the most brutal suffering to the individual. Arbitrary deprivation of nationality is used in the general context of political repression to legally eliminate any person who politically opposes the repressive regime.

Arbitrary deprivation of nationality conveys a series of logistical, economic, social and emotional complications that extend over time and space. It is a type of crime that the victim carries wherever he or she goes.

I was arbitrarily deprived of my nationality by the regime of Daniel Ortega the very same day the regime banished me and other 221 political prisoners from our own country, February 9th, 2023. I had been in prison for almost two years. It was a way of telling us that we were “free” but that we, as supposed traitors to the homeland, were no longer Nicaraguans. The regime wanted us to pass a bad moment the day we were able to finally see the light of freedom. It was a reminder that repression did not end with jail, but that it was going to continue wherever we went.

Arbitrary deprivation of nationality by the Ortega regime came as an extension of a long list of violations against the Nicaragua people. In my case, after being involved in a dialogue convened by the Catholic Church with the regime in 2018, I was subject of eight months of police harassment, illegal house arrests, 24-hour surveillance, travel prohibitions, defamation, threat messages on my phone, hate messages in social media, and several beatings. After announcing my intention to run for president, I was arbitrarily detained June 8th, 2021 and incommunicado for the first 89 days in prison.

The regime put me on trial without due process and denied me a legal defense. I was accused of treason and sentenced to 13 years in prison. This sentence caused extreme pain to my family, my wife and my daughter, who assumed in anguish that they would see me again until 2035. For the almost two years, I was unable to see them in person and denied any type of communication with them.

While in prison, I was subject to degrading treatment, isolation, harassment, and denial of the right to practice my religion. Before my banishment from Nicaragua and declaring me stateless, the Ortega regime had violated 19 out of the 30 rights guaranteed under the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

Later the 222 former prisoners were confiscated of all our properties, houses, businesses, bank accounts, savings and social security rights. The same policy has been applied to 94 opposition members and for the 135 prisoners recently released just three weeks ago.

Now, I want to call the attention on the specific effects that arbitrary deprivation of nationality causes on the individual. First and foremost, the vulnerability and constant harassment from the regime generates suffering. It is a form of torture and transnational repression, as statelessness carries systematic violation of rights and protections wherever the victim goes.

At home, in our case, the illegal statelessness degree was followed by an equally illegal act of eliminating us from the registry of citizens. In addition of depriving us of an valid identification, it affected our children, as they automatically appear as children of a single parent. We have information that their last names have disappeared, thus also affecting them.

Our marriages’ registries have been canceled through legal elimination, bringing additional complications for the hundreds of families.

The confiscation, or the steal of our properties that have belonged to the families for generations, also generated an obvious stress and anxiety, as savings of entire lives have been shattered by a decree.

In a similar way, Social Security contributions of decades have been erased, stripping of the possibility of a pension. For those Nicaraguans already retired, their pensions have been eliminated. More than 70 people have been stripped of their only form of income, leaving them helpless and vulnerable.

Statelessness also removes the Nicaraguan regime responsibility of protection while abroad, and the regime is no longer issuing passports and ID. This complicates the possibility of travel, leaving the person stranded, and without valid identification, with the impossibility of the hosting country to provide assistance.

A very obvious characteristic of statelessness, but extremely heavy to bear, is that the conditions go wherever the victim goes. Thus, the effect of statelessness is suffered as well as in the country of destination, that is, if the victim is able to reach that country. In addition of the sufferings of a refugee or an asylee person, the stateless individual has to deal with no legal protection from his or her consulate. Social services cannot be provided, and social security is denied. The victim cannot continue with education, as the academic records are deleted. This is the situation of more than 60 young Nicaraguan students who lost years of education and have to start from the beginning, if there is a school abroad that accepts them without academic records.

Without any doubt, the worst effect of statelessness is family separation. Leaving the family behind, against his or her will is the source of deep anxiety and distress. The psychological damage is even worse on small children, who do not understand the situation. In the case of Nicaragua, the regime is refusing children to leave the country and meet their parents, as to increment even more the misery. Stripping the nationality, expelling from the country and not allowing family reunion can only be defined as a cruel, and brutal form of international torture.

For some victims of statelessness, the lengthy legal processes countries have in order to grant nationality, sometime taking up to ten years, means that the victim would never have a nationality again. Of the 451 stateless Nicaraguans, more than 20 are above 80 years of age, so it is unlikely that, unless a rapid response happens, they would end their lives as stateless persons.

Fortunately, rapid response came after the announcement of declaring us stateless. Governments of Spain, Argentina, Brazil, Mexico, Colombia have offered their nationality. This act of solidarity is greatly appreciated, especially happening during a moment of huge stress and uncertainty. I became a Spanish citizen on February 22 of this year and many of my colleagues have been granted the Spanish citizenship. We are extremely grateful to the Spanish authorities.

Before summarizing some recommendations, I would like to take to opportunity, as I am speaking to you, to tell you what does it feel to be a stateless person. The legal elimination of you as a person, the erasing of your immediate family relations, confiscation of your belongings, lengthy and costly legal procedures and especially family separation due to incarceration causes anxiety, distress and pain. It continuously distracts your attention to solve problems that most people in the world do not experience: to have a valid ID, to demonstrate that you exist and to reassure that your identity is intact. I had never needed to say I felt Nicaraguan, as I do now.

Statelessness for political reasons, with the additional repression that it carries, sometimes makes me feel angry. Anger at the injustice without any possibility to find justice in my country, as it is precisely the legal system of my country, responsible of such unjust acts. I am aware this is a sentiment to be avoided, as anger affects negatively the person who suffers. I have found peace in praying and knowing that justice will eventually prevail. After six years of documenting the violations of my rights, and with the help of human rights lawyers, I introduced a petition, and I expect that the Interamerican Court of Human Rights would issue a verdict in the upcoming years. This petition make me feel hopeful and most important, that I am using my energies in finding justice for me, my family and my fellow democracy fighters.

When in prison and after suffer innumerable violations, faith gives you strength and conviction. Every night, at the cell, we used the pray the following, which I also have it in my office and pray it:

Take, Lord, and receive all my liberty,

my memory, my understanding,

and my entire will,

All I have and call my own.

You have given all to me.

To you, Lord, I return it.

Everything is yours; do with it what you will.

Give me only your love and your grace,

that is enough for me.

Finally, I would like to share seven policy recommendations that I find useful regarding statelessness.

First, to raise awareness about the international legal framework prohibiting this crime. The 1951 Convention on refugees and the 1954 on Statelessness constitute obligations for signing states to respond to the situation and provide practical and coherent solutions to the problems derived from statelessness.

Second, as statelessness is often combined with refugee conditions, it is important the coordination of international agencies and Governments to identify the cases and provide logistical and legal solutions. In the recent liberation of 135 Nicaraguans to Guatemala, also stripped of their nationality, the immediate response of the High Commissioner on Refugees and well as the International Organization on Migration were very helpful in providing medical, legal, material and psychological assistance to the former prisoners, who suffered innumerable violations. Lessons were learned from our own liberation and applied to the recent process in Guatemala. I hope the lessons are documented so better practices can be applied in future, similar situations.

Third, it is important always to keep the advocacy for freedom and denunciation of violation of rights. Silence from family members of victims contribute to repressive regimes to continue committing such violations. In particular it is important to illustrate the human dimension of statelessness, the suffering of the victims and their families.

Fourth, justice. Arbitrary deprivation of nationality usually comes as a result of a specific legal action, that can in turn be used as evidence of the crime committed by the repressive regime. This makes this particular crime easier to demonstrate than other forms of repression, that usually need the confession of the perpetrators or witnesses.

Fifth, legal support to victims. To carry these cases into the international court system, resources, both material and human are needed to bring justice and reparations to the victims. International agencies, NGOs and Government must provide the material assistance to the victims.

Sixth, promote awareness. Given the large number of statelessness people around the world, more discussion must be around this situation. The role of universities and think tanks is fundamental in the generation of data and analysis that help to better understand the phenomenon.

Finally, it is important to establish an alert system informing potential victims in repressive states of upcoming waves of arbitrary deprivation of nationality.

The Catholic Church can play a very important role in the prevention and elimination of statelessness. First, the Church can provide spiritual assistance and help to diminish the suffering and stress through prayer, compassion and company.

Second it can satisfy material needs using the vast network of communities, schools and dioceses. The Catholic Church can persuade change of actions of world leaders by denouncing the great injustices derived from statelessness.

Finally, it is consistent with the social doctrine of the Church to provide assistance to those who have lost everything, including their land and their nationality.

This is particularly true for the case of Nicaragua, where more tat 125 priests and nuns have been expelled from the country, and by not allowing them to enter back, they are de facto stateless.

Statelessness is, I have stressed, regardless of the causes, the source of an enormous level of distress for families and victims. It is a form of torture, prolonged in space and persistent in time. It can only be solved by either changing the conditions that caused it in the first place, or by attending the problem with practical solutions from Governments and organizations willing to end the suffering of millions around the world.

Thanks.