Religious persecution in Central América

Then and now

March 22nd, 2024

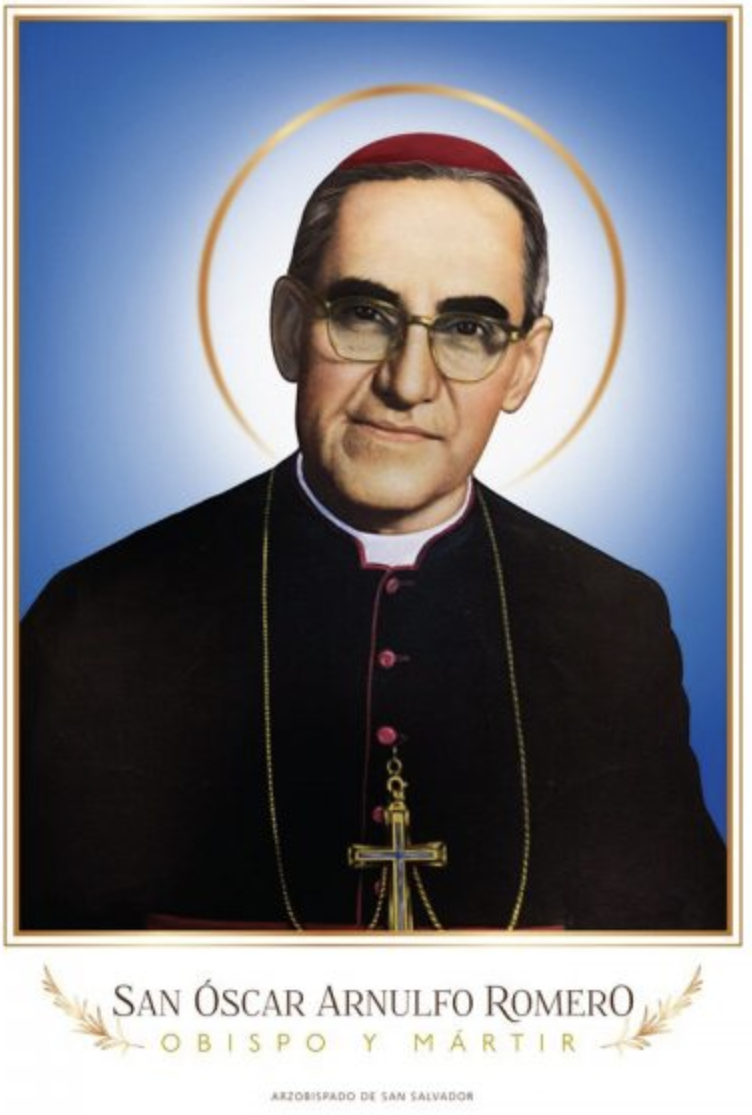

I want to thank the University of Notre Dame, the Kellogg Institute, the Department of Theology and the Cushwa Center for the honor to be here talking about Monseñor Romero and religious persecution in Central America. It is a pleasure to share with you some of my thoughts about the life of Romero in the context of persecution, then and now. It is not easy to comment about the life of a saint, especially a saint who lived in contemporary Latin America, a place full of contradictions and conflicts. Oscar Arnulfo Romero was a man of his times. A pastor who was forced by the circumstances to protect the sheep from the violent wolves. A shy man with a powerful voice whose sermons resonated with hope among the hearts of the poor but at the same time generated hate by the powerful. As Monsignor Urioste said “the most beloved by the oppressed majority and the most hated by the oppressive minority.” Romero became a saint through martyrdom. Like any human being, he was afraid of being tortured and killed. On many occasions, he referred to his fears about that possibility. Despite that, he continued with his powerful sermons to denounce injustice. This is one of the most prominent characteristics of his personality, and a great legacy, that he knew the risks, but his commitment to God in the defense of life was stronger than his fears. Romero faced the attacks of the powerful, who ultimately killed him. He faced criticisms even from his beloved Church. Bishops accused him of being responsible for promoting violence. He came out very worried from an audience with the Pope, who asked him to have a better relationship with the government. It must have been agonizing for him to be pulled and pushed by all these forces. It was the challenge he had to face as the supreme authority of the Church in his country, El Salvador. Monsignor Romero is, unfortunately, a representative of a long list of martyrs of the Church, starting from the early martyrs killed by the intolerance of the Roman Empire. In Latin American, there has been constant persecution against priests, many of whom have lost their lives in the defense of the dispossessed. Antonio Valdivieso, Bishop of Nicaragua, was stabbed to death in León, Nicaragua, my country in 1550 by order of Rodrigo de Contreras, the Governor, and son-in law of the first dictator Pedro Arias de Avila, better known as Pedrarias. Valdivieso’s opposition to encomienda, a repressive system that mistreated natives, had created animosity amongst the politically powerful. Valdivieso had a close relationship with Fray Bartolomé de las Casas, who also was instrumental in establishing the laws of 1542 that protected the natives, amid opposition of the landlords. Valdivieso had written to the Crown in 1544: “The origin of the problems is Contreras, who is a cruel governor. Nobody can venerate God nor his Majesty without risking his life…” We can change the name of the dictator, and Valdivieso’s sentences can be applied to today’s cruel dictators around the world. Romero, in a letter to Pope John Paul II in 1978, described the Salvadorian situation as one of “injustice and institutionalized violence” which had made the Church the object of persecution for denouncing injustices and the abuses of power….” Forty-four years after his assassination, the Church continues to be attacked by the powerful. Nicaragua is the most recent and probably the worst case of persecution against the Church in recent years. The persecution includes bishops, like Rolando Alvarez who spent almost two years in prison and Silvio Báez, who had to go into exile. The repression extends against hundreds of priests, nuns, entire orders and charities, and the catholic people of Nicaragua, who cannot participate in processions and whose churches have been emptied of priests, who had to leave the country. There are obvious differences between the past and the present. Comparing El Salvador 44 years ago to present Nicaragua should be done with care, as contexts and historical circumstances are different. Despite the differences, there are some things in common, starting with the victims. Since its beginning, Christianity has been above all, a faith in the defense of the poor, the abandoned and the marginalized. Vadivieso, Romero and the bishops in Nicaragua, all have in common the defense of the victims from powerful individuals who, using force, repress human dignity, eliminate freedoms and violate rights. In the case of Romero, one victim made a fundamental impact on him: Jesuit Priest Rutilio Grande. They were close friends and respected each other. Grande’s assassination led Romero to a transformation. He saw in the body of his assassinated friend the suffering of those murdered before and after him. Romero’s decision to follow Grande’s job must have been difficult, as he moved away from one type of priesthood to another. He broke with his past but at the same time returned to his past. “Yes, I changed, but I also returned” he told Father Jerez, reminding him of his humble origins. For his entire life as a priest Romero loved the poor and the abandoned. He helped them by collecting contributions from the rich, alleviating their consciences, and giving them to the poor, alleviating their sufferings. He always helped the poor from a protective perspective, from compassion. His transformation led to a more personal relationship with the poor, this time, as victims. “To Feel with the Church” was the motto Romero chose when appointed archbishop, which coincided with Grande’s assassination. With this slogan, he wanted to show his deepest commitment and connection with the suffering of the poor, who are the ultimate victims of injustices. Father Rafael Moreno Silva, a Jesuit, in his recent book, describes Romero transformation in three steps: First, his reencounter with the poor was from a structural perspective, that is based on a social justice perspective. The poor were no longer the subject of assistance, but rather, he understood the roots that caused poverty and saw them as victims of an unjust system. I would call this first stage the return to his origin moment. Second, Romero understood God’s call to action in the clamor of the poor. He possessed the grace to connect with people. Cardinal Angelo Amato in the beatification mass said “God conceded the bishop martyr the capacity to see and listen [to] the suffering of his people”. This is what I would call the Rutilio Grande moment. After Grande’s assassination, Romero said “This death has meant not a change in my ideas, but an intensification of my commitment to the poor and the defense of the rights of the Church”. To a Jesuit priest, Romero wrote “if they killed Rutilio for what he was doing, it is for me to walk in his same path”. In other words, not only the killing transformed the mind of Monsignor Romero, but it was also a call to action, an action that he took with courage, determination, despite knowing the risks. The third step of Romero’s transformation, according to Father Moreno, is that Romero discovered the political dimension of the Christian faith. Romero, in Lovaina, said “The political dimension of the faith is no other thing than the Church’s response to the needs of the real world in which the Church lives….”, adding later that this was the true “option for the poor, embodied in their world, to announce the good news, to give them hope, defend their cause and participate in their destiny”. This is what I would call the feel with the Church moment. This last step is probably the most complex one, as it have been the subject of criticism. Romero responds: “The radical truths of the faith become real truth when the Church immerses in between life and death of the people. The Church presents itself: to be in favor of life or death, with great clarity we can see that it is not possible to be neutral. Either we serve to the life of Salvadorians, or we are accomplices of their deaths.” The country was being torn apart by mortal sin, and the Archbishop was creating awareness of the situation. The position of Romero may seem logical today, but we must be aware of the historical context and the fact that he was the supreme authority of the Church in his country. At that time, he touched important interests in the country. Romero always refused to call his transformation a “Conversion” because as Father Moreno points out, a conversion implies having failed in Christian fidelity or his obedience to the Vatican. Romero referred to his transformation as a process of knowledge development. In in a private letter he wrote: “A time has come in which we, as Christian’s have to respond to God’s call” To Cardinal Baggio at the Vatican, he wrote “if I gave the impression of being more prudent or spiritual it was because I truly believed it was the way to respond to the Gospel, as the difficulties of my ministry had not been as demanding of pastoral strength as the circumstances of being an Archbishop”. Romero understood power, and the power of the Archbishop came with more responsibilities, the responsibility of taking care of a large group, as pastors do. Romero’s transformation occurred at a time when the Church had also transformed, after the Second Vatican Council a decade earlier. The Latin American Episcopal Conference in Medellin was also key in defining the position of the Church in one of the most unequal places on earth. The Church as the people of God was assumed, and the role of Christians was redefined. Christians must transform the world to achieve justice. Here in this world. The Church assumed a position regarding the situation of the poor as victims of violence. It was no longer possible to stay away from such issues. It moved from a paternalistic, charity-oriented perspective, to see the victims of injustice as subject of their own destiny. We cannot conceive the transformation of Romero disconnected from the transformation of the Church. In the canonization process, Romero case went to the Congregation for the Defense of the Faith, which after a rigorous, five-year-long analysis, stipulated that Romero’s positions, recorded in thousands of hours of homilies and interviews, matched the orthodoxy of the Church. He was thus able to enter into the complex world of today without deviating from the Church’s teachings. I think this is good evidence that Romero was not manipulated by political forces, which no doubt influenced his thinking, but was able to maintain a prophetic voice. Romero has been accused of being manipulated by the left. Others claim that he was softer against the left than against the right. I think Romero based his fight against abuses and he opposed violence from both sides, and it is a fact that the abuses came mostly from the military. The polarization in the country, polarization that continues today in a different form, clearly made his work more difficult. Romero was also brutally attacked and slandered by the economically powerful. Most members of the economic elites in Central America put their interests above anything else. I know this firsthand, as I come from an elite family in the region. At the same time, I also believe that politicians tried to use the figure of Romero for political advantage. I also know this firsthand, as I am also a politician. The fact the Romero initially supported the second military junta, probably his worst mistake, can be used as evidence that he tried to maintain a bridge of communication at all times. The conditions in Latin America continue to be of great inequality. Income and land inequality are high, in El Salvador in particular, where land is scarce. The violent displacement of peasants from lands owned by the rich was a very important factor in the violence that culminated in a civil war. Romero did not start the violence, as some have accused him. Violence had existed for a long time. One could argue that the violence of the civil war could had ended earlier in the presence of Romero, such as in Nicaragua, where Cardinal Obando played an important part in the cease fire. Monsignor Silvio Báez tells us that it is time to put aside this type of conversation regarding Romero “There is no denying that there has been incomprehension, misunderstandings, and prejudices with respect to the figure of Monsignor Romero, it is time to accept him within the Church and in the light of his martyrdom, the Church can be stimulated and renovated, in order to be less diplomatic and more prophetic, a Church, as Pope Francis says “poor and for the poor”. What Romero did was to raise the voice of the voiceless. His clear, strong voice and eloquence captivated the entire nation. He used radio intelligently. His homilies captivated the country. He used the pulpit and technology to denounce the atrocities. His reports were well documented and for years were the only way victims could have their cases heard. In Romero knowing the risk, I want to point out to another characteristic of him: he was not detached from reality. Romero was constantly informed about every episode of violence in the country and he paid attention, knowing all the details. Romero was particularly careful to be clear about the circumstances of the violence. Romero was never questioned about the accuracy of his reports at every Sunday mass, reflecting how well prepared and informed he was, thanks to a dedicated and professional team of supporters he was able to gather. By informing the faithful of the events of the week in his homily, Romero connected the Gospel with reality. “The Gospel”, he said “is the great defense, the proclamation of all rights (Homily January 8th 1978.) In his homily of June 4th,1978 he made it explicit: “To proclaim the Gospel without relating it to reality implies no problems, but the beauty is to illuminate with the universal light of the Gospel our own Salvadorian miseries and victories. Is the beauty of the word of God, because in this way we know that Christ is taking to us.” The Bible also says something about risks. Saint Paul made it clear about the difficulties of the Ministry of committed followers of Christ. 2 Corinthians: “We are hard pressed on every side, but not crushed; perplexed, but not in despair; persecuted but not abandoned; struck down but not destroyed. We always carry around in our body the death of Jesus, so that the life of Jesus may also be revealed in our body. Yes, we live under constant danger of death because we serve Jesus, so that the life of Jesus will be evident in our dying bodies” (2 Corinthians 4:8-11). As time passed by and repression intensified, Romero became more aware of the risk. In his dairy he wrote, two months before the murder “I put under God’s providence all my life and I accept with faith in him my death, regardless of how difficult it may be…. Despite my sins, I have put my trust in Him and others will continue with more wisdom and holiness the job of the Church and the Homeland.” In his last homily, a day before his assassination he said, “In the name of God and of this suffering people, I implore, I order, stop the repression”. This was taken as a call to insubordination by his enemies who gave the final order. He accepted the risks, with a sense of hope, not fatalism. To a fellow priest, he once said “To take side with the poor, is going to cost us blood” “Until when?”, asked the priest. “I do not know. We have to keep an eye on the sky and we must read the signs”. Romero visualized that his death did not mean the end of the fight for justice, and that others would follow. In another conversation, someone asked Romero: “Monsignor if they kill us all one by one, kill the priests until there is nobody left, what would we do?” He said “As long as there is one Christian, there is the Church. The one standing is the Church and must continue.” Romero clearly left a profound legacy in the next generation of priests. His commitment for social justice and his ultimate sacrifice shaped the thinking and actions through the world but especially in Latin America. Báez said: “The martyrdom of Romero, as a result of his faith, which led him to be at the side of his martyred people and raise his voice in defense of the poor and social justice, teaches us that we cannot give life without sacrificing our own….Nobody works seriously for God’s kingdom and justice if he is not willing to face the risks, rejection, conflict and persecution suffered by Jesus.” Nicaragua Romero was assassinated 8 months after the Sandinista Revolution in Nicaragua, an event that caught his attention, especially in relation to peasant organizations and land reforms. Like in El Salvador, in Nicaragua the Catholic Church experienced internal conflict. As opposed to El Salvador, though, the hierarchy of the Church stood firm behind Monsignor Obando y Bravo, a conservative. The “popular church”, as it was called, entered in frank contradiction with the bishops and generated a conflict, which persisted for decades. The Sandinistas received vital support from young students and members of Christian base communities in working class neighborhoods in Managua. This support was fundamental to the forces that ignited the insurrection that overthrew Somoza in July 1979. The Nicaraguan Bishops saluted the revolution in a pastoral letter in November of 1979. But the support was short lived. A year later, the bishops warned about the dangers of authoritarian regimes using the Church. The Sandinistas responded disrespecting Pope John Paul II in a solemn mass in Managua in 1983. The Pope reacted by suspending a divinis the four priests in the Sandinista government and more importantly, appointing Archbishop Obando as the first Central American-born Cardinal in the history of the region. More powerful and influential, Cardinal Obando’s sermons played a crucial role in the elections of 1990 which Ortega lost to Violeta Chamorro. When Ortega won in 2006 he appointed Obando as head of a Reconciliation Commission, inspired by Desmond Tutu’s Commission, with the difference that Obando did very little. The powerful Cardinal had become a diplomatic figure, appearing every time at the side of Ortega. In the meantime, Ortega continued with a project to amass the most power possible. He used the Supreme Court to reform the constitution, which allowed him to be re-elected. He became more repressive. Basic human and political rights were violated, independent media harassed, and opposition leaders persecuted. Massive protests erupted on April 18, 2018 as a result of an unpopular reform to the social security system. Ortega responded to the protesters with real bullets. The violations of basic rights in my country were denounced by the Bishops of Nicaragua from the beginning, and their messages resonate with that of Monsignor Romero. Two days after the protests began, when the police had killed dozens of young students and protesters, Monsignor Silvio Báez, in the metropolitan Cathedral said: “Do not fall into intimidation, do not let go because of violence, your protest is just, and the Church supports you. We not only support you, but we urge you to continue… your cause is for social justice, believe in the force of Peace and nonviolence”. Baez added on another occasion: “A society without prophets becomes hard and entrenches in corruption. The Church is willing to risk everything in order to stay alongside the victims of violence. The Church condemns those who attack and kill because they have the weapons.” Later Baez was forced into exile, as credible sources indicated that there was a very high probability of an attempt against his life. At the airport leaving the country, he told a group of people that went to say goodbye: “I wish Nicaragua would become a society founded in social justice, a society in which true peace will flourish.” During a march on Mother’s Day in 2018, Ortega’s armed forces fired against protestors, killing 19 young people. The University of Central America, run by the Jesuits, opened its gates to protect thousands of people running away from snipers. This action saved many lives, but it meant a death sentence to UCA, as Ortega later confiscated the university. Bishop Rolando Alvarez, one of the most prominent bishops, in the context of the protest said: “the Church is not there to fulfill anybody’s fancies, the Church is here to defend the people, because the Church is the people.” Again we can see here the similarities with Romero’s words two decades prior. Monsignor Alvarez suffered harassment, arbitrary arrest and was sentenced to 26 years in prison and banished from his country. His immense popularity was not tolerated by the regime. Rosario Murillo, Vice-President and Ortega’s wife, justified that the detention of Bishop Alvarez “was needed to guard the peace, security, and tranquility of the Nicaraguan families.” On February 9th, 2023 a group of political prisoners, including myself, were transported to Managua International airport and asked if we agreed to go the United States or to remain in prison. All of the prisoners signed, except one, Monsignor Alvarez, who was immediately transported to the infamous Modelo prison, where he had to stay for an additional year until he was put on a plane with 18 other priests and sent the Vatican. Alvarez’s decision to stay with his people, although in prison, is a clear testament of commitment and courage. A true representation of the Church’s sacrifices and the difficulties Christ’s followers have to endure. In the last five years, members of the Catholic Church have been victims of stigmatization, physical aggression, harassment, exile, prohibition to re-enter their own country, passport confiscation, censorships, subject to fake trials, condemned, incarcerated, banished from the homeland, and stripped of their nationality. Even the papal nuncio was expelled. Churches have been attacked, images burned, entire religious orders expelled, schools and universities confiscated, accused of money laundering, their bank accounts frozen, divested of legal status, and church-related media outlets have been confiscated and eliminated. Ortega is trying to extinguish the only remaining voice of hope in the country to attain absolute power. Since the banishment of Bishop Alvarez last January, none of the banished priests have spoken or been seen in public, a clear indication that Ortega has used terror again to silence their prophetic voices. The religious persecution against the Church is the result of hate, just as in the case of Romero. It is hate against the position of the Church in support of the suffering people of Nicaragua. The voice and actions of the Church are uncomfortable to power. Ortega attacks the Church in Nicaragua for the same reasons Jesus of Nazareth was attacked, for the same reasons Romero was attacked. Persecution against the Church will continue. Processions are still prohibited; priests are still harassed. More priests would end up in jail if their sermons, monitored and recorded by government spies, contained references to justice, freedom, or peace. If Ortega can do this against priests and bishops, one can only imagine the level of abuses and repression against the common citizen of Nicaragua. Nicaraguans currently live under a state of terror. This is precisely the same question Romero was asking himself while in front of Grande’s dead body. I am not here to criticize the decision of the Vatican to negotiate the freedom of the bishops and priests, their banishment from Nicaragua and their silence. The Ortega regime referred to these negotiations and agreements as “…direct, frank, prudent and very serious dialogue, based on Good Faith and Good Will”, while at the same time prohibiting Holly Week processions, 5,000 processions to be exact. The Vatican diplomacy has a 2,000-year experience and I hope the position will result in something positive. During the last six years, I have had the opportunity to share time with a lot of priests and bishops. I have had the chance to share their thoughts and insights, even to enter their personal lives and sufferings. Six priests shared prison with us, from August 2022 to January 2023. In the last two months of our ordeal in prison, the dictatorship relaxed some of the rules. We were prohibited to pray for almost a year and a half. Suddenly, we started to pray out loud, and the police officers did not silence us. We began a daily tradition of praying with the priests in the cell next door that helped us to keep strong and hopeful. A preferred one was the Prayer to St Michael: “…..by the power of God, cast into hell Satan and all the evil spirits who lurk about the world seeking the ruin of souls.” No wonder why the police officers did not want us to pray loud… I want to comment here on something personal about praying. Sometimes, in Latin America to be a “rezador” is not positive in the sense that the prayers do not do anything more. Romero himself was criticized for being a rezador before his transformation. I found in praying hope and strength. I prayed so much for my liberation every day, and God granted it. I felt touched by Him and it redefined my conception of praying. Instead of the ritual I learned at an early age, praying became an intimate, personal moment of connection with God. Going back to the Nicaraguan Bishops, Monsignor Baez from the start of the crisis, reinforced Romero’s idea, expressed by Romero in a homily in March 1980, when he said “Nothing violent can last long”. Baez added that “it is important to demand from those who have the weapons, to protect the integrity of the people. Avoid anger and violence, as they take away the better of us, nothing violent would last.” “The offenses we are suffering” Baez said, “make us stronger, and aggression is the strength of the weak.” While I was at a national dialogue with the regime, Baez instructed the team of negotiators in a private meeting to “lean on the strength of reason but not reason by force, and to follow the way of Jesus, who had sacrificed for us”. “Allow yourselves to be questioned by the people, who are the ultimate protagonists. Organize small informal assemblies, let ourselves be touched by the people, be friends with the poor.” Contrasting with all the terrible things that I had to suffer in the last years, such as prison, harassment and exile, I can only feel blessed to have received such a private, and intimate teaching from Bishop Baez. They have provided me hope and spiritual strength. Nicaraguan Bishops such as Baez and Alvarez, many other priests and several orders such as the Jesuits, understand today, as Romero did in his days, that the victims are the result of institutional violence. The lack of rights and inequalities occur in the context of a structural perspective, of a system in which there is no rule of law. A system of concentration of power in few hands, extracting resources and power from the majority. The bishops responded, in the case of Nicaragua, to the cries of mothers who lost their sons in the massacre, the majority of them I should add, coming from poor, Sandinista homes. Finally, the bishops, priests, and orders responded to the need of a Church conscious of the political dimension of the Christian faith, not based on political activism but from the Gospel, which can tell us a lot and specially, as Romero said, when it can be contextualized to our realities. Final thought on El Salvador and Nicaragua In the 44 years since the assassination of Romero, El Salvador and Nicaragua passed through dramatic and costly civil wars that led to more than 125,000 people dead combined. Both countries went to a peace process that led to disarmament of the irregular forces, and free elections. Both countries regressed in democracy and are now governed by totalitarian regimes that have crushed any form of opposition. Both presidents were able to get reelected by illegal maneuvers involving their respective Supreme Courts. In both countries there are violations of human rights, and independent media have been harassed and forced into exile. The civil wars and conflicts in Central America were in part spinoffs of the Cold War. The United States, the Soviet Union, Cuba and the Communist block sent huge amounts of resources to fuel war. Unfortunately, the region received very little resources to rebuild, both physically and institutionally. The peace agreements, the transition protocols, the democratic reforms were not enough to build a new, better society. Corruption, violence, democratic backsliding, and widespread poverty characterize Central America today. With these not-so-happy results, one can wonder, what is worth all that sacrifice? Is there hope? While the problems facing Central America today are multiple, I can see three fundamental problems that must be addressed: First, the lack of rule of law. In Latin America and Central America, the law is used as a weapon to protect privileges and attack opponents and dwarf competition. If we do not put justice above all powers, we will continue harvesting messianic dictators who think they are the real saviors. Romero on the administration of justice said: “What is the Supreme Court doing? Where is the transcendental role on a democracy of this branch of government, that should be above all powers and claim justice for all? I believe this is the key to a great deal of the pain of the people.” Second, social injustice. As long as we have a system that denies education, health and basic services to the population, our societies will remain poor. It is in this sense that the confiscation of the university and social projects of the Church in Nicaragua is generating a real tragedy. Third, economic inclusion. As long as the system is used to protect economic privileges and repress economic freedom and the promotion of a creative system friendly to innovation, transformation and value added, these economies will remain exporters of raw materials, something they have been doing since Valdivieso’s time. We need the Central American economies to grow and develop, and become exporters to high valued products, not exporters of human beings. Romero’s sacrifice and the current persecution in Nicaragua is a testament of how far institutional violence can go. How the concentration of power can inflict pain and suffering. It is also a testament of how resilient priests can be in the face of such repression. In conclusion, to feel with the Church, Romero’s motto, reminds us of the Church as the people of God, people that must be protected. Romero’s legacy, followed by the Nicaraguan priests but also elsewhere, is a demonstration of the political dimension of the Christian faith. The priests as spiritual leaders who remind us, Christians, of the importance of the Gospel, and to convert the teaching of Christ, into political action to solve the problems of this world. Thank you.